My last memory of my mother was when I slipped into the west door of her bedroom in time to stand between Father and Beckie Weatherston, as they folded her hands in death and pulled the sheet over her face. Dr. Driver stood at the other side of the bed. Since then I have always felt cheated that I had no mother as my friends had. I was the eighth child born to Lyman Stoddard and Electa Philomelia Dixon Skeen; the older ones being in order of their birth: Lyman Jr., Charles, Emma Jane, Joseph, Jedediah, Electa and William Riley. The latter ones were: David Alfred, Sabra Alice and Isabell Electa. Mother died with the twelfth child. The child was not taken as would have been possible in later days.

My last memory of my mother was when I slipped into the west door of her bedroom in time to stand between Father and Beckie Weatherston, as they folded her hands in death and pulled the sheet over her face. Dr. Driver stood at the other side of the bed. Since then I have always felt cheated that I had no mother as my friends had. I was the eighth child born to Lyman Stoddard and Electa Philomelia Dixon Skeen; the older ones being in order of their birth: Lyman Jr., Charles, Emma Jane, Joseph, Jedediah, Electa and William Riley. The latter ones were: David Alfred, Sabra Alice and Isabell Electa. Mother died with the twelfth child. The child was not taken as would have been possible in later days.

We did not have doctors for childbirth in those days, middies officiated. When I was expected the one who had been practicing was ill, the new one, Mrs. Elizabeth Murray Moyes, had not finished her training so a neighbor, Phoebe Richardson, assisted at my arrival. I have often wondered, since learning this, if it was the reason for my being the odd and lone one. I must have been ill as a youngster for I remember staying with my Grandmother Dixon at times for a few days. I was 8 years old just one week after my mother died. We had, in my childhood, one of the finest homes in Weber County, with apple and peach orchard, long rows of native and red currants, prunes, etc., but never a nice vegetable garden or many flowers, too many horses and cows around however.

When the first camp for the settlement of Plain City was made on March 17, 1859, it was on the corner where the old home stands. Lyman Skeen rode his pony from Lehi, went back for his family and goods, Lyman remained here. Grandfather took up the land for Lyman and just before they were married, built two adobe rooms 16 x 16 and 16 x 11 feet, adobe, three feet thick in the walls. The nails used were square iron ones. In 1946, when a window was put in the East room it was found that the adobes were in a very good state of preservation. Other repair work and plumbing installed at that time showed that big rocks were first put into a not too deep excavation, then stringers cut from poles were put on, after that floor joists and single 6 inch boards for the floors. As the family increased, the first two adobe rooms were replaced by frame rooms, added as needed. This part of the house was changed and remodeled many times. We had a west porch and a lean-to type of kitchen at the east end of the house. At the south, across a narrow passage, and even with west end of the house was dug a deep cellar, rocked up, with door to west. Over the cellar was a large granary with the platform and door at the south. On the east was a shed room building which we called the Meat House, in it Father cured the meat. Later this room was partitioned and the south end used as a place for the family buggy, one-seated, on which father drove his beautiful horses. His driving teams were the envy of many men in the county.

I always teased to sew on the old machine mother had, so when a new one was bought, she kept the old one which I coaxed her to put under the trees and the, while tending Isabell in a clothes basket, I sewed carpet rags from a box. This is how I sewed my middle right finger. Just about the time Charl was married, in the fall of 1890, we had a dressmaker at the house making dresses for Emma and Electa and I was very much hurt that none was in sight for me. While on an errand I went to the store kept by Peter Folkman and wife, and since they had some of the material left, I bought and charged to father six yards. It was dark brown, diagonal weave serge. I took t home and announced that I was having a new dress too. When father came in from doing the chores, there was a consultation that included me. Next morning I took the material and sold it back to Mr. Folkman. My dress came along in due time, and I had learned a lesson, we hoped.

At that time, and for many years afterward, we secured yeast for making bread from Annie Neal, the wife of our postmaster. She made it in great stone jars. We took a small pail with as much flour as we needed and traded it for a like amount of yeast. How I loved to sample the yeast from the pail. It was a joke that at times (even though I always allowed a little extra) I would come home with so little that I had to make a second trip. Across the ditch and east of the house we had a woodshed facing south. We had a woodlot down by the Weber River and in the fall and winter when crop work was done, Father with the hired men (we always had two or three) and the boys when they were not in school would saw down the trees and then saw into such lengths as could be put on the bobsleigh. They were then hauled home and into the yard through a big gate east of the woodshed and rolled off. During the winter they would be sawed into wood lengths and split into quarters for the heater and smaller pieces for cook stove. We bought practically no coal in those days as it was a luxury. We all loved our big Franklin heater. It had a foot bar across the front and a big door made of heavy tin with a handle at top. We took the door down to feed the stove and when the wood had burned down to coals, Father would pop corn in a long-handled popper, a big pan of it. A half pound of butter was poured over it with a little salt. That with a pan of red apples provided a center piece for the long table at which we studied, and a wonderful snack before we went to bed. Father would sit in front of the heater in his big arm chair and hold Alf and me on his knee while he sang all sorts of wonderful songs.

April 20, 1891, was the day that sorrow first struck our home. Sabra Alice, just younger than Alf, died as a result of scarlet fever complications. I remember how quiet the house was when I wakened, I got up, dressed myself in my Christmas dress, a light tan with plaid collar, cuffs and sash, my new shoes and hair ribbon and started for school. I had just cleared the woodshed when father came to the door and called me. As I turned back he told me what had happened. I said, “Well, do I have to stay home for that?” Just one week later, April 28, 1891, which was Sabra’s fourth birthday, Mother left us. We were at the supper that night before Sunday, when she suddenly left the table and went to her room. Samuel Wayment and his wife were having supper with us so Mrs. Wayment went in to help father. We were sent to bed as usual. Monday morning I was sent to Mr. Knight’s with a pan for some rhubarb.. I had just reached the barn across the street when I heard father cry out. I ran back to the house and slipped into the west door of my mother’s room just in time to see them cover her up. She died of placenta praevia, or flooding before the birth of her child. Father’s grief was terrible- left at 40 with 10 motherless children, the oldest, Lyman Jr. was 19 and Emma only 16. The question of housekeeper or hired girl was a big one. Emma was very particular and it was hard to suit her with the housework. Since I could walk along I had trailed father, or Pa, was we called him, everywhere I could. If his hand was empty I held to his finger, if he had his hands full I gripped his pant leg – eight or ten times a day he would turn me to the house, give me a little spat and send me to mother. I would go where I could watch him from a corner of the house and if I heard him laugh or some neighbor came to talk with him I would go back and join the party. Many times right after our loss I would find him in the barn with his heads in his hands, shaking with sobs – I would run for Charl, who lived just across the street and to the south and get him to come. He would get father to go for a ride or interest him in some of the horses or work around the barn. Across from the house and at the north we had a big cow barn with a machine shed at the north, hay barn at the east and cow stanchions at the west, then a big corral with pig pens at the side and a huge horse barn with room to drive a hay rack in through the big doors. It had a workshop in one end and stalls for father’s fine horses at the west side. The barn was built as well as a house would be these days, and shingled.

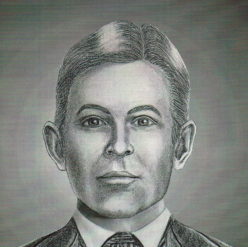

Not long after mother’s death, father’s friends persuaded him to go to England with William Gampton (a widower friend) who had relatives in London. He left us in charge of Lyman Jr. and Emma. Charles looked after the horses and the farm with the help of the younger boys. Father was terribly seasick and did not travel too much over there, spent most of this time with the sister and brother-in-law of Mr. Gampton. They were gone two or three months. He always told us that when he went to Europe again it would be after they put a bridge over the ocean. We had a series of hired girls, housekeepers and help by the day. Emma was so painfully clean and fussy she broke her own health and had a terrible time keeping up. She would wait until we were all tucked in bed at night then scrub the big kitchen floor of pine boards until it was white as a bread board. There was no linoleum for floors at that time. I have thought many times that life would have been unbearable if the neighbors in the ward had not been so good to us; we were always invited in and treated most kindly by those with whose children we played or when sent upon an errand. Seems to me I was always alone and running from one place to another. I went with some of the girls my age on a weekday, out to the big ditch and was baptized and confirmed a member of the church on the ditch bank. It was late in May of 1891. My report was the only family record. The church books were burned in a home so neither Riley, Alf, or I had any church record when we needed it. Electa took the family bible record with her and it was lost or destroyed. Father was a very handsome man with black mustache, and was well-to-do by the standards of that time, and was much sought after by widows of the county and various matchmakers. One widow came out and left her poodle “Dollie” to be taken care of while she went on a trip. She insisted the dog have a bed of its own (in this case an old baby crib) and that it have special food. We have never had a dog in the house and it soon soured the whole family on that widow. Lyman Jr. taught school after he graduated from the University of Deseret. We were never allowed to take our lunch to school, which was in the old Hall three blocks east and one south of our home. One day, after weeks of pleading, I was permitted to take my lunch, though Lyman came home for his. After we had eaten, some of the older boys caught a mouse by the tail and chased us. They hit me on the back of the back and my neck and shoulders with it. I began to scream and when Lyman returned I began to shake, could not control my hands or the twitching of my face. He took me home and Dr. Driver told us I had *St. Vitus Dance. It came on me in January of every year until I was 16. I was usually taken from school late in January and lost the rest of the year’s work.

During the late summer of 1891, father met Annie Skelton who was the sister of Aunt Nora, the wife of father’s half-brother Joseph. He was the son of Rhoda Laurence Skeen. Annie was one of seven daughters and one son of Mrs. Skelton who had been widowed many years before. The only work at that time for girls who must make their own way was housework for families who could afford to hire them. Annie had been working in Salt Lake City and she and her sister Mary made their quarters with their sister and brother-in-law, Frank Dunfords. Annie’s birthday was March 7, 1864, therefore she was only 28 when she and father were married February 7, 1892. We came home from some affair in the ward to find them in the parlor with Bishop Stewart, who had married them. My first fuss was that I was moved from my bed in father’s room where I had slept since I was so unhappy and cried so much for mother. Alf had been sleeping with father. Undertaking the job of mother for ten children, several of them grown, was not light task under any condition for a woman of 28, and it was hard for father to be fair and keep a balance of some sort. We were not angel children by any means and I am sorry to say much could have been avoided in the adjustments of the older children if some of the neighbors and friends had been more open-minded. “Electa’s children” were pitied openly by her friends with whom she had been a great favorite and by her family as well. And I think we were not helped too much by some of his former lady friends. I must have been a terrible trial at this time for I had St. Vitus Dance so badly I had to sleep on a bed made on the floor back of the living room stove. I could not share a bed and could not stay on one. I twitched so that I could not feed myself and could not walk straight. During the winter the whole family suffered a plague of boils, big blue ones. I had a carbuncle under each arm at the time, and a gathered right middle finger. Jode and Jed were continuously making fun of me, tripping me and then refusing to help me up. Finally Charl and Mag took me to their home where I was treated like a baby. I had to be fed and dressed and watched all the time. For recreation they would put me in the bobsleigh on hay covered with a big fur robe and take me to the field when they fed the cattle, then on sunny winter days, I could sit in a wagon box, bundled in blankets and fur robes, and watch them split the wood. One of my terrors was watching Charl break a horse. At times they would pass the house, the horse bucking and jumping with its head down, would go over the wire fence mother of the house and many times wee were sure he had been killed. Father’s fine driving horses were nearly as bad. The boys would hitch them to the one-seated buggy and one stand at the head of each horse until father and his passenger (and he always had a rider) were seated. Then, when they released the horses, they would dash around the corner and maybe run a mile before he got them down to the gait at which he wanted to drive. He had a sorrel team, then a black one. It was wonderful to be the one selected to go to town with him or even for a ride. One of my greatest joys from age 10 to 16 was to be permitted to go to Ogden with father. We would leave home in time for him to attend to business. He was prominent in politics, a Republican died in the wool, though he always voted for the best man on either ticket. He was County Commissioner for many years and in his later days was Road Commissioner. He would drive to the Nelson Livery Stable, leave the horses for the day and hand me $5.00 or more, if I needed shoes or a dress and then tell me when and where to meet him for lunch. We would go to a restaurant and have a good meal. Usually he would have a friend or one of our neighbors he happened to meet and whom he invited to join us. When he left me again he always reminded me to check my cash to see if I had plenty and tell me what time we would leave for home. My first stop would usually be at the fancy work counter at Wright’s and then to buy a paperback novel or magazine. There were no movies so for the time I was alone I would find a bench in the park or sit in Horrocks Brothers store. This was our family headquarters and we were always welcome there.

Father was always called to help in sickness among the townspeople, as well as with his own brood. His diagnosis was usually ‘worms’ and the remedy was a tablespoonful of castor oil, with three or four drops of turpentine taking inwardly “Ugggh!! Then we had turpentine rubbed lightly on each side of the nose and in the little net in the throat, even at times put on the pit of the stomach to urge the worms to leave. Strange as it seems, we always got well. He got himself a pair of forceps, too, and pulled teeth for the children and some adults, for miles around. Many times he would pay the child 50 cents to have the tooth pulled. My first tooth he took out as I slept in my chair at night. He was always good as a veterinary, people came with sick horses, cows and he even prescribed for their pigs.

Because of my nerves I was never permitted to join with the other young folks in games or dances during the year. Occasionally I was allowed out on Friday night but most of the time I had to go to bed quietly with all the rest, except for the babies, were out and Father and Annie were in bed. I planned and executed many escapes through the hall door at the south or even out of the bedroom window to join Mabel Knight, Alminda Lund and others and get out for a while. Most of the times I would be seen by some member of the family who tattled and it got me punished, usually a spanking in the morning. I used to love to go to Uncle Will’s on Sunday. His girls all had ponies and we could ride them. I always found that Dad had an apple limb switch saved for me on Monday morning (we called it my apple limb tea) and my philosophy was that I got it anyway so why not have the fun.

I do not remember, in my childhood or early girlhood or since, one act of kindness, help or consideration from Jode, J.D. or Electa. We did not have playgrounds, recreation directors, or even nursery books to amuse us. “Let” would get us involved in some game or dangerous play then be the first to run to father and tattle and stand by while we took the punishment. I learned never to deny a trick or lie out of it if I was guilty, but we had a lot of conflicts where I was accused wrongfully. Riley, who was born August 4, 1881, and was almost 10 when Mother died, suffered from a speech impediment – stammering. We all teased him and would mimic his frantic attempts to talk. The hired men, older boys and even we younger ones tormented him. I think this was his great trial and destroyed his self-confidence. It made him very shy and resentful. He, with the neighbor boys, used to catch fronts in the slough below the house, put them in a box and father took them to town to the Falstaff Cafe, which was very high class, where they were considered a great delicacy. When he was put to hoe the potatoes or corn he would work a while then go to visit Aunt Min Geddes, Mrs. Lund or Mrs. Olsen or maybe Auntie Nicols. We were all trained to be home promptly for our meals. We were all well cared for in the material things, food, clothing, a good comfortable home and education, but there was not too much show of affection in the home. We had such a large family it was mostly a case of ‘survival of the fittest’ and I sometimes think Riley and I got the least of the ‘fittest’.

Mrs. Saray Coy who kept a store on the hill where Blaine Skeen now lives, was very good to us. She had been a good friend of mother’s and helped her with washing and cleaning. Her husband did not approve but she came anyway. Their farm was near our field so mother cooked the dinner for both of the families and when she saw (from her west porch) the men leave the field she would dish up for Mrs. Coy and then take the dinner and hurried home. After she started the store she sold penny candy and many a time the chicken coop was raided to get eggs for candy, sometimes we got two pieces for one egg. Even the setting hens lost a few eggs I’m afraid. Mrs. Coy was blind in one eye and she used to drive a horse and buggy to town very early one or two times a week with vegetable and eggs for a few special customers. She wrapped the lines around her knees and knitted all the way there and back. One day she passed the house all dressed up. She was a Josephite and they had services in a small brick church in the north end of town; Episcopal, I believe it was. I asked her where she was going and I looked through the picket fence at her. She said, “to church”. I watcher for her as she came back and asked if there were many people at her church. She said, “no one but her.” I said, “well what did you do when no one came?” She replied, “I sang, prayed, sang again, read the bible, sang, prayed and came home.” This was always a lesson to me.

The rest of the history is by Junior Charlton

Aunt Mae gives a fantastic and comprehensive detail of early life and surrounds about grandfather and the family in early pioneer history. From reading Aunt Mae’s life sketch, it seems to end when she was about 16. I will attempt to complete her life as I see it.

Mae, upon completing her eighth grade, which was all the requirements she needed at that time of history, went to the University of Utah to continue her education. She lived with her sister, Electa.

According to Emma Jane’s history, she and her newborn daughter, Iona, who was born in November of 1899, went to live with her two sisters, Lell and Mae, in Salt Lake City, when her husband was on a mission to England.

Mae, having missed so much school due to illness had a struggle with University study. She settled into the field of bookkeeping and finance. She stayed in Salt Lake, living with her sister.

She was courted by several young men and became acquainted with William W. Rawson, whom she took a fascination to. Their relationship grew stronger as time went on. They became engaged and were married on February 3, 1903 in Pocatello, Idaho. On December 12, 1903, a son Merlin L., was born to them. They were very proud of this young boy and their love grew stronger each day. In the fall Merlin became extremely ill and he passed away on October 26, 1903. This was very devastating to them especially his father. He was looking for someone to lash out at and this is usually someone close to you. This put a great strain on their marriage. The accusations and resentment began to accelerate to the point of separation. The reconcilable problem could not be resolved which ended in divorce.

After Mae healed she interviewed and acquired employment with Ogden State Bank which was located on the southeast corner of twenty-fourth and Washington Blvd. It was later purchased by the First National Bank, torn down and replaced by a new building. Mae worked for First National Bank where she was given more responsibility and later became secretary to the directors. During the depression years, late 1920’s and early 1930’s, she made it possible for many to acquire loans through the Federal Land Bank. She was aggressive and successful in what she did.

After her divorce she returned to Plain City to live. By some means Mae acquired her Father’s estate upon his death in 1933. Mae, upon acquiring Lyman Skeen’s home made three apartments in it. Ruth Rogers Charlton told me that after Harold and she were married, they lived in one of the apartments. Many of Aunt May’s nieces and nephews lived there. Many school teachers also, would live there during the school year.

Mae was a beautiful seamstress and was good at knitting and crocheting. She made many beautiful pieces that she gave away to relatives and friends. Nancy Rhead Hansen told me that it was Aunt Mae who taught her and many others how to crochet.

Mae met and was courted by Harry D. Brown of Farr West. They were married on March 11, 1932. After their marriage she quit work and moved into his home on the corner of North Plain City Road and Higley Drive. Harry had lost his wife and he had several small children left in his care. As time moved on their marriage became unstable. I have no idea what arrangement was made, but after the last child was married she moved out.

[Ed note: This is where the history ended. We can piece together part of the rest through her obituary. At some point she bought a home in Ogden at 1052 Doxey, which was where she was living when she died. Lyman Cook, the Bishop of Plain City First Ward and a nephew, conducted the funeral. She is buried in the Ogden City Cemetery next to her baby, Merlin.]